It’s been a busier than usual fortnight and so the newsletter here is a little later than usual while the next podcast is likewise somewhat delayed. That podcast is a technical one (lots of science and heavy on details). It’s a reflection on the next set of readings from and reflections upon of Chiara Marletto’s book “The Science of Can and Can’t” where I’m up to chapter 6 called “Work and Heat”. This is a chapter very specifically about a well known area of physics which is the subtopic called thermodynamics. Thermodynamics is a particularly interesting area of physics because within it we have something called the first law of thermodynamics - which is energy conservation, perhaps one of the first laws of physics learned by students at school. It is something most people are at least familiar with even if they cannot provide a precise definition. But people have heard of the law of “energy conservation” but as Chiara and David say that law is actually deeper than what other laws might be and so it can be called a principle - it is something other laws that exist or even might be discovered in the future must conform to. A purported law that violates energy conservation has its work cut out for it and in fact it likely refuted at the first hurdle. Or in other words: if your newly discovered law violates the principle of the conservation of energy then that itself is a criticism of your law and remains a valid criticism absent a good explanation of why the principle does not or should not hold.

Now the second law (of thermodynamics) is something else again. This law is a strange one in physics because no one knows how to derive it from anything more fundamental as they do with other laws. The history of science is kind of replete with this kind of thing. We have these things called Kepler’s Laws (for example) that govern planetary motion. Now without going into details about what they are the fact is they were expressed as 3 distinct laws in around 1619 - about 6 decades before Newton published his universal law of gravitation. Now the latter is a deeper law and from it you can derive Kepler’s laws. And of course now we have General Relativity so we can make a few assumptions that might not strictly be true but so far as approximations go we can derive Newton’s law of gravity and hence Kepler’s laws. Now truth be told the word “law” here is a misnomer. They’re misconceptions - but that’s a whole other topic we could get sidetracked by. My point here is that in theory no that’s ambiguous - in principle - no that’s even worse. My point is that in science when we find a deeper theory we can show how the higher emergent “laws” or “theories” can be derived as approximations in some cases to the deeper law. Or sometimes as laws that simply fall out as nothing but logical consequences of the deeper law. But the second law of thermodynamics is not like this. The second law of thermodynamics cannot be derived from quantum theory - the theory of how matter behaves in terms what the particles are actually doing such that there’s an irreversible process. The second law seems to give an “arrow to time” some physicists are fond of saying (namely it describes how things tend in this direction and not that direction unlike with dynamical laws of motion) or in terms of general relativity which is spacetime. The classic example is that we witness eggs smashing onto the floor but never the pieces gathering themselves up again into a whole egg. Why can’t quantum theory of general relativity explain this?

There seems to be nothing in our account of time (in the theory of spacetime which is general relativity) which, once again, prefers things move in the direction of increased disorder or entropy (or broken rather than whole, untracked eggs) - put it how you like. So the second law has always been this kind of empirical law which is to say: we observe it to hold and never to be violated. But as to why exactly - we don’t know. The second law is a statement of the break in symmetry between the past and the future - a symmetry that is inherent in all other physical laws. They are said to be “reversible” or time symmetric. The future resembles the past when it comes to dynamical laws of motion whether those laws are classical or quantum. But the future does not resemble the past as we know: yesterday is not the same as today and tomorrow will be different again. But why in terms of physics at the fundamental level? We don’t know. Something to do with the second law. But what exactly? What is happening with the particles that in all other circumstances are just obeying dynamical laws that make no distinction between motion in this direction that happens to be forward in time and motion in that direction which just so happens to be backwards in time. Put another way if we watch some ensemble of particles interacting - keep it simple and make it just two particles crashing into each other - no physicist (or anyone else for that matter) who watched such a video (presumably this is a very high frame rate electron microscope super high resolution video of particles that are very massive colliding) - would be able to say whether you had reversed the video or not. It may as well be forward in time as back in time. This is utterly unlike a video we take of a car crash. Or anything else in the macro world. But particle interactions? What is hiding in that video that governs the tendency towards disorder or increasing entropy?

What Chiara has done is explain how constructor theory might be a new way of approaching the second law in terms of what is possible and not possible. So we’ll be tackling that in the podcast rather than here right now. I feel I’ve already said too much! My sense is that the podcast will stretch over two episodes so I’ll leave for now more talk about all that for next week.

Now onto one of my favourite politicians - which is a strange phrase to utter because I don’t tend to have favourite politicians. Indeed I have something between cynicism and deep skepticism about all politicians as a working hypothesis. I am often concerned about people who seek such a position - because what they’re seeking is power over their fellows. But there can be exceptions to this cynicism about politicians. One would be Winston Churchill because he was the right man at the right time that the free world and Enlightenment needed to take power, have power and wield power at a time when the worst possible kinds of politicians had risen through the ranks elsewhere in the world. It’s a shame this needs to be said these days and presumably not to my audience here and now - but Churchill more than any other person should be the one credited with the defeat of German fascism and hence Adolph Hitler and the Nazis. Or perhaps more precisely I should say won the second world war in Europe and drove German fascism from power. I don’t think European Fascism was entirely destroyed in truth by any measure but it was very much reduced and minimised and sidelined as a significant political force even if the underlying philosophies that drove it persisted - but that’s another matter.

Churchill was also praised by Karl Popper as a philosopher - as an epistemologist in particular and this is something I’ve mentioned before on ToKCast. And so for that reason too Churchill is near the top of my list. But as to living politicians - well there’s no one in Australia to speak of that impress me and right now we are almost at the end of the Australian Federal Election campaign so we’ve had more than the usual number of political heads on screens. But in the UK Daniel Hannan ever since I first encountered him delivering a speech somewhere or other on Youtube I think about Brexit has always been excellent. He speaks clearly, he answers questions directly and he has a deep understanding of the relevant history, philosophy and culture of liberty, wealth creation, the Enlightenment and so on. He wrote a book called “Inventing Freedom” - which I really should add to the list of books I discuss. So I have almost nothing but praise for Lord Hannan of Kingsclere as he is at the moment. He is not shy about standing up to the excesses of the left and right side of politics. He was right, for example, to recently pen an article that was titled “Why are we so afraid of sex differences in education?”. This is an important issue. The issue basically is that policy makers see it as a problem that boys choose physics more often than girls do. When I have worked in education it was always seen as a problem for girls. Girls were supposed to choose more physics and more engineering and more mathematics. And the underlying assumption was that the reason they never did was something to do with discrimination (or that vacuous terms “unconscious bias”). Now the fact boys chose psychology and sociology subjects and even artistic and dramatic subjects at a rate lower than girls was (and is) not typically seen to be a problem. And this then fed (and feeds) into universities of course: universities have begun to discriminate on the basis of sex or gender when it comes to entrance into some courses. Girls are courted into physics courses and all else being equal and the number of places limited, where two candidates are the same or almost the same and only differ by gender: well the girl will be admitted ahead of the boy. Now this should not be seen as a problem. If all the obstacles are removed - all the inherent discrimination removed - then humans should be allowed to freely choose rather than being cajoled into courses or provided carrots and sticks in order to rig the numbers to be 50/50. Indeed it’s well known, I think, now that in places that claim to be the least sexist (The Scandinavian Countries) - so places where all the obstacles to girls entering whatever occupation they like are removed - the sex differences in job choice widens. For example https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20190831-the-paradox-of-working-in-the-worlds-most-equal-countries The fact is that males choose this kind of area of study and females choose that kind of area of study. Now here’s where people who take an interest in this kind of thing go wrong on both sides. Some will see that fact and go: aha! A moral problem. Even when discrimination is removed, girls are still not choosing to become civil engineers and instead are choosing - freely - to become child care workers and this is a problem. We need to incentivise women to make the correct choice more often. Or at least the correct choice until half of all engineers are female. Or something like this. So that’s one side. And on the other side we have the people who say: aha! A problem in need of a scientific explanation that we already have in hand. The Science Says “Male and female brains are differently structured and therefore boys like playing with trucks and girls like playing with dolls.”. Which is basically what is being said sometimes. Now if we just accept: it’s curious and we don’t fully understand why this is going on but it’s not a moral problem that calls for us to react with policy too.A problem really is discrimination. But once that is extracted out of the picture, why are we still concerned?

Now I’m going to sidestep the concern that anything like occupation or academic interest area or subjects chosen in high school should be 50/50. We could equally look at the distribution of ethnicity vs interest in physics or hair colour vs interest in physics or body mass index vs interest in physics. I just don’t think it’s interesting or it matters. It’s legitimate to ask the question and at the same time of no consequence.

So I am with Daniel Hannan, I would think, on all that. However on this issue like some others, Lord Hannan has become enamoured by evolutionary psychology. Now I notice this because I’m a fan of his and I follow him on social media so I tend to encounter the arguments he invokes that rest on the assumptions from evolutionary psychology. And the reason I bring it up is because I think his arguments stand without the evolutionary psychology. More than that not only do they stand without it, they are undermined by invoking them. Now it’s not just him and he is in good company - so I’m focussing solely on the content of the idea here. It could be anyone writing in this vein and to some extent I can’t blame a politician who is used to taking “expert advice” - even one as switched on as Daniel Hannan on this topic simply because it is the prevailing view in the scientific culture right now (wrong though it is). And that view is something like: the human brain is biologically adapted and therefore the evolved physical structures of the brain determine (more or less strongly) the thoughts we tend to have. And thoughts include things like “choices about what subjects to take in high school”. Which is a strong claim. And in this case we’re focussing on the differences in male and female human brains rather than, for example, the structures we share with chimpanzees or other primates, say (which is often what underpins some of this evolutionary psychology stuff). And I am going to completely ignore some important science here (the same science that the evolutionary psychologists or those who want to insert neuroscience into education here might) - and that is that it seems to be the case that there are no biological differences in anatomy when it comes to male and female brains anyway. A follower of mine from Japan helpfully linked to an article from Nature about this. Now interesting as that is, it’s actually irrelevant to the deeper argument which applies whether the brains of males and females are identical or completely different in structure. This is about function and what they are functionally capable of - and once capable why people freely make the choices they do in some given culture.

Now some say on this point when it comes to genetic determinism - the idea that genes determines your behaviour or at least genes determine brain structure which determines your behaviour - well it’s not strictly determine in the way that the strength of gravity determines the rate at which objects fall to the Earth. Or it’s not determine in the way that the quantity of hydronium ions determines the pH of a solution. But it’s something more like “influence” or “shape” something like that. It’s a little softer than “strictly determine”. Of course we never know by how much the genes determine behaviour exactly and most importantly of all by what mechanism the evolved structure of the brain or the DNA determines or influences or shapes our thoughts. Absent an explanation we are in a world of non-explanatory “science”. Science is the place we seek explanations. If there are differences between male and female behaviour or life choices that are said to be genetic then absent and explanation of how genes determine behaviour we aren’t doing science. We are guessing wildly. We are saying “here: grass cures the cold. Just try it.” But why? How? What is the mechanism? A hand waving dismissal of “well it’s clear that there are differences between males and females genetically so of course this is why the behaviour is different” does not cut it. One may as well wave a dismissive hand to the heavens “Well there are literally hundreds of chemicals in grass. At least some of them will be hostile to the growth of cold viruses. That’s just science.”

Daniel Hannan has written and spoken a number of times (eg https://www.conservativehome.com/thecolumnists/2017/10/daniel-hannan-the-modern-politician-must-learn-about-psychology-and-how-evolution-moulds-our-minds.html ) about how we evolved on the African savannah and in places that were deprived of abundance and for this reason we tend to hoard stuff and for that reason we don’t like free trade. So our genes for hoarding determine our thoughts about capitalism. That’s basically the case with some nuance. Now I reject that. But not because of an irrational anti-science stance. The opposite. I reject it because it is at odds with our best explanation on the topic - the deepest explanation of this. Evolutionary psychology can claim whatever it likes but if it wants to be science it cannot violate laws of physics. And it is claiming to - or insofar as it is not claiming to violate physics then it is vacuous.

The deepest explanation that is relevant to this whole issue of male and female brains and our evolved brains and so on is known is computational universality. Now the thing is this: people are minds. Their minds explain things. And their capacity to explain is universal. Now this is another kind of universality I will come back to. For now, let’s just focus on the mind and say that the mind is controlling the behaviour of the person. The mind is not the brain in precisely the same way the computer game is not the computer. The computer game runs on the computer. But the computer itself can do a literally infinite number of things. It’s universal - a universal computer. Our brain on the other hand runs a mind. And the mind controls behaviour and we have a literally infinite number of behaviours we could engage in.

Now how does the mind control the behaviour of a person? Well it does this by taking in some input (which basically means using one’s senses to “gather” data - which to a Popperian means interpret data), making some decision (which to a Popperian means something like comparing that interpretation to a theory we have about the world) and then delivering the output - the behaviour. Now it’s no mistake that this way of describing things resembles what a computer sitting on your desk does. That is not because a human resembles a computer in some ways. It is because a person IS a computer in some ways. And the way a person is a computer is that their brain is a physical system - some hardware running some abstract creative program (some software). It is, literally, a computer. It’s not an analogy. And the brain, like all physical systems can be simulated by a universal computer. If we could simulate the action of the brain perfectly then it would generate a mind. And I would go further and say it would generate a conscious mind. Now again, here is where many people - even many so-called rationalists pull the breaks and cease being rational. They want to say something like: well, we don’t know what consciousness is therefore “we do not know if consciousness comes along for the ride here”. But, again, taking our theories seriously, even if we have a mystery as to what consciousness is precisely, does not mean it - the phenomena that is consciousness - can violate laws of physics. Or at least that is not a good working hypothesis. Why not stick with what we do know and apply it to what we don’t know and see where that leads? In this case what we know is that the universality of computation applies to human brains which are known to be conscious and therefore a stimulation of such a brain will also be conscious because consciousness is known subjectively and objectively to be part of the output of functioning human brains and therefore a simulation of a functioning human brain will simulate its output too.

It is rather like if we take a computer - computer B and we simulate the behaviour of computer A perfectly then computer B is doing everything computer A is. So if computer A is running a flight simulator then computer B must also, by definition, be running a flight simulator. So too with a human brain. IF a human brain gives rise to a mind (and consciousness) then if we take a computer and simulate the behaviour of the human brain we will get a mind within it.

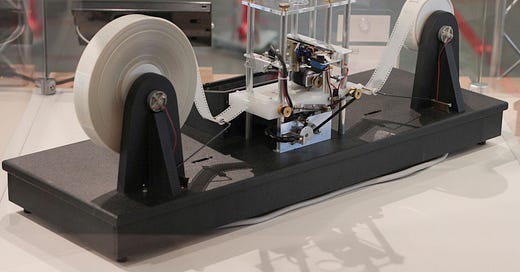

(Above: A “Turing machine” - the basic device to which all classical computers can be reduced to. A long tape with a head that can read and write symbols on the tape according to instructions (the software) that it follows).

Now you might object to this. You might emotionally feel that this cannot be true. You might object that a person is more than this. You can stamp your feet as hard as you like: the thing is that this is what we know (fallibly!) because of computational universality. It simply is the case that all physical systems are computable - they can be simulated by a universal computer. This is provable and has been proved. If the system obeys the laws of quantum theory (and anything made of matter does) then a computer can be used to simulate the behaviour of that system - in principle. Now I hasten to add this does not make it that system. A simulation of a bullet is not a bullet as I have said before. But that is because a bullet is not “computing” anything - the central qualities of a bullet are all purely physical - not abstract. Unlike with, say, a song which is abstract. It is a pattern. You can have the musical piece written down as a score. You can have it recorded as a video. It can be put on a cd or it can be played live. The song is not made of atoms. Stories are not made of atoms. Software is not made of atoms. These things are particular patterns that can be represented in different physical substrate. And the human mind is one such kind of abstraction. For now it is only represented in human brains but there is no law of physics that says it cannot be represented elsewhere in other physical forms. This happens to be the basis of the argument for artificial general intelligence. That has to be possible because we exist. We are general intelligence that exists. It takes a special kind of mysticism to assume that brains - wetware - or even human brains in particular are made of a matter that is so special it cannot do elsewhere precisely the same thing as other matter. That’s merely an assertion at odds - once again - with computational universality which says whatever can be output by that system doing information processing there can be done elsehwhere by some other system in principle. And the claim our brains are not processing information is just false. They are. It’s not a denigration of humans to say we obey the law of gravity - we can’t fly. Or that we we need to eat because we obey the law of conservation of energy. Likewise it’s no insult to say: we obey the laws of quantum theory and our brains must be computationally universal to do what they do because they are computing stuff. They are computers. Of a kind. Special yes. But still - they obey the laws that apply to all other computers.

A brain is a physical system. If you reject this then you reject naturalism. You are in a world of mysticism and pseudoscience. You reject the notion that science as we understand it is the way in which we best understand the world. You are opting for a form of supernaturalism at least in this domain. Or perhaps you think “well that’s what you think now but tomorrow it might be wrong” and in that case I agree with you. Of course! We can always be wrong. That’s just fallibilism. As much can be said for anything anywhere anytime. “You can’t know Joe Biden is the President of the USA right now. Perhaps he just died and Kamala was sworn in secretly? You can’t know!”. Trivia nights would bet short affairs if that was the standard. We do know.

Atomic theory might be wrong. Evolution by natural selection, the theory of tectonic plates, the theory of the inflationary big bang, everything we know could be wrong. To a Popperian it goes without saying. But if we want to understand NOW the best of what we understand NOW about people then computational universality applies to people’s brains as much as it applies to any other system out there.

Now on top of this we have explanatory universality. And that means we can explain anything in principle. Once again denying this just means some things are inexplicable by us. Which is the standard retreat of the religious mystic. Well: maybe you can’t understand God. Or why God caused the flood. Or what the universe means. Some questions are off limits. Very well. It’s hard to argue against those who deny humans can understand anything. They’re pessimists. So long as they are not getting in the way of people who say: no we can solve that problem - are can explain that thing - then I have no issue. Of course such people don’t keep to themselves. They do get in the way. Religious and supernaturalists who want to cordon off what questions people can ask and answer do tend to want to control policy and so on.

So what has this to do with anything? Well the evolutionary psychologists claim that neuronal structure and inherited characteristics determine what thoughts we have. So hardware determines software somehow. But this just is not true for any other computer. Each year the structure of the latest MacBook Pro changes somewhat. But it’s function doesn’t - it can still run the same programs. It is still - approximately universal. And indeed it can run the same programs more or less as any PC can (if the program has been written). We should say it can complete any task any other computer can - given enough time and memory.

Human beings are the same in that we can do - mentally - what any other human being can do. So why don’t we? Interest and time. Life is finite and people have interests. Sure everyone kind of says they would love to be able to do what Arthur Benjamin can do. But very few people can. Is this because they are mentally entirely incapable? No. They just lack interest. If they really really tried they could learn the techniques. https://www.ted.com/talks/arthur_benjamin_a_performance_of_mathemagic?language=en

This is not genetics. There is nothing in Arthur Benjamin’s DNA that codes for multiplying 542908 x 3409530 in his head without the help of pen or paper let alone a calculator. Yet he can do it. How? Because he learned the technique. Is the technique in his DNA? No. There is DNA for building the brain structure. Does his DNA code for a structure that allows for this? Yes: but then it codes for that in us too. And that structure is a universal computer running a universal explainer. In Arthur Benjamin’s case he used his universal brain to do a specific thing: become really good at a particular area of mathematics that almost everyone finds easy to understand as impressive and is somewhat envious of. But the same is true of virtuoso chess players and pianists and trivia champions and so on. Human beings - people - have this wide variety of abilities because of the thing that does not vary between us: our universal minds. If we want to explain the differences between us we have to explain that one thing we have in common: a mind that can do anything anyone else can. Our mind is genetically determined to do one thing: follow its own interests and change those interests over time as we learn more in a completely unbounded way. A preference for mathematics and physics is not in the genes. It is not in boys brains more than girls brains. An ability to play piano is not to be found more in the DNA of people from that culture than this culture. There are differences - absolutely. We don’t know why they are all there and is that really important. What is important is understanding something far more deep than the superficial specific differences between people even if those differences appear to be grouped according to gender or ethnicity or whatever else. What is important is we are all people and what a person is, is a universal explainer. And that is unique in the universe and explains why we have this variety that we do. That’s an amazing quality. And it’s far more poorly understood than evolution is. Our choices are not determined by evolution. That’s quite an absurd notion. Our choices are literally choices. We choose freely because we, uniquely in the universe create knowledge. And no matter what evolution has determined - or rather what has evolved our there in the biological world - it is only though us we understand anything. And on understanding anything at all we can choose to do anything not prohibited by laws of physics about that thing. Genetics does not make some boys and some girls choose to do physics. Boys and girls choose to do physics because they really are making a choice. And left to choose rather than being coerced and cajoled and in some cases even guilted into it, they will tend to choose this rather than that at different frequencies. Why? Because they exist in a culture and sometimes people react to their appearance in a certain way and none this is a bad thing so long as everyone is free to choose and not coerced.

PS: Now there is an interesting postscript to all of this. The Tweet from Daniel Hannan that prompted all of this basically linked to his article that I’m responding to here but the tweet itself read “There are some aggregate differences between male and female brains. This is considered uncontroversial by neuroscientists but unspeakable by politicians.” Which as we have seen may or may not be true (cf: that Nature article referred to and linked to earlier) - but it’s irrelevant for reasons of universality. And it was why I tweeted in response that “What is correct about this argument is *not helped* by scientism. Brains are the wrong level of analysis. They’re the hardware.

We are minds - the software (which is universal).

More males do physics. But not because their brains have a special structure. That’s a red herring.” And in response to this David Deutsch himself remarked that “Universality (both computational and explanatory) presents severe problems for some rarely criticised institutions.

For example, exams (poorly) measure *something* but not underlying merit. So various corrections are applied. But given universality, what is underlying merit?” Which is quite right too. We have this notion that examinations - whether school based or university based or, the classic IQ test are measuring something. In the case of the latter I’ve long argued that the I should stand for “Interest” and not “Intelligence”. After all I’m one of these people who argues for an understanding of intelligence that is basically a binary: an entity can either create explanations or explanatory knowledge - explicit explanatory knowledge (in which case it is intelligent) or not. This matters for things like SETI - the search for extra terrestrial intelligence. Now I’ve written a lot about intelligence and IQ tests and so on and have grated they are predictive. They’re just not explanatory. And if a thing is solely predictive but you don’t know how or why it is, again, we’re outside science. We’re doing something else: it’s science in form only and this is something that just plagues psychology as a discipline at times. IQ tests might very well measure, for some substantial number of people who take the tests - interest in responding accurately to IQ test questions. Look if there’s one thing I can tell you from my time as a teacher there is a large- certainly non-zero number of people - students - who exist and who are very bright but go into examinations and tests and assessments and are utterly bored by the whole thing. They do not care. The exam does not capture their intelligence. At all. It’s capturing their interest. I have taught students in mathematics who I have told my colleagues are brilliant in whom I have seen brilliance (you know young kids who can find mathematics exhilarating - I remember one girl who was able to do prime factor decomposition - constructing factor trees - in the blink of an eye with almost no upper bound on how big the number got. Well of course there was - but my point is this girl was a whizz at like the age of 12 or something at taking a big number and giving you the prime factors like oh? 29250? Quick flurry of work and then writes: 2 x 3^2 x 5^3 x13. Now as anyone who knows the technique - ok, not so impressive. But this is after having just learned the technique. And again for even large numbers. But the thing is this same student had no interest in tests. So would never perform well and for other teachers - well because she spent a large part of each mathematics lesson doing her art (which I never personally minded) this would upset them. So they sent her to remedial mathematics classes and they remarked she wasn’t capable. And they always looked at me quizzically when I said she was astonishingly talented. So was she or not? Well I knew she was and I didn’t need a test. Indeed I knew the test was a terrible tool. This girl simply was not interested in doing your test. She would rush through any test and then cover the blank pages with her sketches and doodling. This was a creative intellect that the school was actively harming and while I was responsible for her: sure. She had some reprieve from being told to do this that or the other and to perhaps find some fun with something like mathematics when she wasn’t as heavily coerced into it. Anyways it’s examples like that and my own experience with IQ tests that tell me these things cannot possibly capture something like “degree of intelligence”. It’s something else. Like in the case off IQ tests on the occasion I have officially sat down and done one which was when I went for one of my first ever jobs as a security guard the head of human resources at this company - he was a psychology PhD as it turned out. But among other things he tested everyone with a standard IQ test. And I remember thinking as I solved the puzzles that: oh. This is fun. This is just like those puzzles I do in books I buy and magazines and newspapers I read. Which shape doesn’t belong. What happens when you rotate this one. Which word belongs in this group and so on. So I had fun and treated it like a game. But on the other hand I also knew the feeling of getting bored at some point. Now what if you were bored right at the beginning? What if you were more nervous? What if you’re always bored and always nervous in these situations? Well you’re not possibly getting an accurate reading of intelligence. Especially of my student there who literally won’t care.

So here’s the challenge, then. You want to hire someone and you need some criteria and you’re interviewed as much as you can and looked at credentials. Credentials - another story in itself. Well maybe you need a proxy for “won’t get bored easily by doing some mundane task”. Which actually is a pretty good trait to have in a security guard. Can you sit here for one hour and just focus on a single thing? So the IQ test might actually get at that. Of course you’re focusing on the test. Can you focus on security cameras or on customers in this store? I can tell you no: that skill to focus on one thing isn’t generalisable.

Or what if you have a limited number of places at your university for taking people into a chemistry course? How can we assess your interest in chemistry? Well maybe past performance is some indication of future commitment? Well that looks like induction unless of course we have a good explanation why your past performance was good. Maybe you’re just pleasing mum and dad and your teachers all previous high marks in chemistry are just an outworking of that feeling of needing to live up to the standards of adults. And once that’s taken away at say university you’ll not perform so well and worse: you never were interested that much in chemistry. Just in completing chemistry tests to get good grades so that like Lisa Simpson people would praise you for those excellent grades. Remember when the teachers went on strike and Lisa turned up at her teachers house demanding to be graded and when she was she reacted as if she was a drug addict who had just received their hit?

But look, yes: you have a limited number of places in your chemistry course. You have a spot that needs filling in your chemistry laboratory. Name this thing where you need to make a judgement call about who will fill this position. And if you admit: well tests scores are terribly flawed but I’ve spoken to 15 of these people and I can’t split them. Except on grades. What else to do? I have no good answer except that if time is a factor and you need too explain this decision to someone with, let’s say, the final say - better grades is better than anything else. Or higher IQ scores is. But we can admit all of that imperfection and never admit: actually intelligence is a sliding scale and actually performing well on some examination might actually indicate precisely something of the opposite quality to what we want. Namely it might indicate very high knowledge about how to meet predefined outcomes and to learn pre-existing knowledge and it might also indicate a poor ability to question any of that pre-existing knowledge, think outside the box and really make progress creatively. It could mean all that. But for every urban legend of the genius scientist who failed high school we have other examples of genius scientists who also topped their classes across the board in every test. So there’s that as well.

What to do about tests and exams? Clearly we must move away from that in school. But that’s just a special case of we must move away from coercion when it comes to learning of any kind. Forced to attend lessons, forced to undergo assessment, forced to turn up at a particular time and listen to a particular person give answers to questions never asked - well it’s all got to go.

And here on this side of the ledger - that anti-coercion side - it can be two steps forward and one step back at times. But that does mean we’re moving forward and incremental dismantling of a terrible system is somewhat more palatable to the powers that be that saying, like the proverbial fire-sale sprier “Everything has got to go!”.

Well that’s more than enough for now. Until next time!

Share this post